Understanding Allosteric Stabilization of pMHC by Peptide Ligands Through Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Abstract

Objective:

The dynamic interaction between peptide ligands and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules plays a critical role in regulating cytotoxic T-cell response. While peptide-free MHC molecules are known to be highly unstable, the precise mechanisms underlying peptide-induced stabilization remain poorly understood.

Materials and Methods:

Classical molecular dynamics simulations of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A*02:01 in both peptide-free and peptide-bound states were performed. Each simulation was conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Protein energy networks were constructed using pairwise amino acid interaction energies computed from resulting trajectories. Network analysis was performed to reveal the roles of residues in protein stability.

Results:

The analysis revealed that peptides with weak interactions at the F pocket failed to enhance connectivity at the HLA-β2m interface, thereby compromising the overall structural stability of peptide-loaded MHC (pMHC).

Conclusion:

These findings shed light on the mechanisms by which peptides stabilize MHC molecules and modulate their dynamics, providing insights into T-cell receptor recognition and the regulation of immune responses.

Keywords:

Major, histocompatibility, complex protein, stability protein, dynamics immunogenicity antigen, presentation molecular, dynamics structural, bioinformatics protein, energy, networksIntroduction

The adaptive immune response is a critical component of the immune system, providing highly specific and long-lasting protection against pathogens. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes play a crucial role in this response by eliminating infected or cancerous cells (1,2). Cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize and kill target cells through the interaction of their T cell receptors (TCRs) with peptide-loaded major histocompatibility complex (pMHC) molecules presented on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (3). This interaction is highly specific, with the TCR recognizing both the peptide antigen and the MHC molecule, a phenomenon known as MHC restriction (4,5).

There are two classes of MHC molecules: MHC class I (MHC-I), which presents endogenously derived peptides to CD8+ T cells, and MHC class II (MHC-II), which presents exogenously derived peptides to CD4+ T cells (6). MHC-I molecules consist of a heavy chain, a light chain (β2-microglobulin, β2m), and a bound peptide. The heavy chain comprises three domains (α1, α2, and α3), with the α1 and α2 domains forming the peptide-binding groove. The peptide is anchored within this groove, while β2m interacts with the binding groove and α3 domain of the heavy chain, stabilizing the overall structure (7,8).

Protein dynamics play a critical role in the interaction between TCRs and pMHC complexes (9). Both MHC and TCR molecules exhibit inherent flexibility, which is essential for their function (10,11). The dynamics of MHC-I molecules thus influence peptide binding, presentation, and T cell recognition. Once bound, the peptide ligand itself can also modulate the dynamics of pMHC, affecting its flexibility (12), with significant implications for TCR recognition and subsequent T cell activation (13).

The stability of pMHC complexes is also essential for efficient TCR recognition. Peptide ligands were shown to stabilize pMHC by interacting with specific pockets (A, B, C, D, E, and F) within the peptide-binding groove (14). Different peptides modulate the dynamics and flexibility of pMHC complexes in distinct ways, thereby altering the protein’s energy landscape and influencing overall stability. Notably, pMHC stability has been positively correlated with its flexibility (15).

Furthermore, β2m binding and dissociation have been used as accurate measures of pMHC stability, highlighting the importance of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-β2m interface (16,17). These findings suggest that peptides can allosterically affect the HLA-β2m interface, thereby influencing the stability of the pMHC complex. However, the exact mechanisms underlying this allosteric effect remain largely unknown.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide detailed insights into the conformational changes and interactions that govern pMHC stability and flexibility (18-22). Given the potential of MD simulations to unravel the allosteric mechanisms by which peptides stabilize pMHC complexes, this study aimed to investigate these mechanisms using MD simulations and shed light on the complex interplay between peptide binding, pMHC dynamics, and TCR recognition.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Peptide-HLA*02:01 Complexes

Explicit-solvent MD simulations were performed using GROMACS version 2023.4 (GROMACS Development Team, Stockholm, Sweden) (23). Hydrogen mass repartitioning was employed to enable a 4 fs integration time step (24). Each system was simulated three times, with each simulation covering a total time of 750 ns. The AMBER99SB-ILDN force field (25) was used in combination with the TIP3P water model (Jorgensen Laboratory, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA).

Systems were neutralized with sodium/chloride ions to a final ionic strength of 0.15 M. Simulations were run in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble with the pressure maintained at 1 bar and the temperature at 310 K. A non-bonded interaction cutoff of 12 Å was applied for van der Waals interactions. A conformation was saved every 5000 steps.

Initial protein structures were obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB; Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Piscataway, NJ, USA) (26) with accession codes of 3UTQ, 5N1Y, and 5C0F (24). The peptide-free system was obtained by simply removing the peptide ligand from the MHC structure deposited in 3UTQ.

Root Mean Square Deviation and Root Mean Square Fluctuation Analysis

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) was calculated for each simulation to assess the deviation of the molecular structure from its initial conformation over time. The calculation was based on alpha carbon coordinates, with the first frame of the trajectory as the reference. The equation used for RMSD calculation was as follows:

where N is the number of atoms, xi is the position of atom i in the current frame, and xiref is the position of atom i in the reference frame.

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) was computed to quantify the atomic flexibility around their average positions during the simulation. Root mean square fluctuationfor each atom was calculated using the following equation:

where T is the total number of frames, xit is the position of atom i at time t, and xi is the average position of atom i over the entire simulation. Root mean square fluctuation was computed using only the final 500 ns of each trajectory.

Essential Dynamics Analysis

Essential dynamics analysis (EDA), also known as principal component analysis (PCA), was performed to identify cooperative global motions of amino acids. First, a covariance matrix (C) of alpha carbon coordinates was computed:

where X is the coordinates of all alpha carbon atoms, with a dimension of 3N by 3N. <X> denotes the average position matrix over the equilibrium portion included in the RMSF analysis as well. This matrix is then diagonalized to identify its eigenvalues and eigenvectors:

Here, λ is a diagonal matrix consisting of eigenvalues, and T denotes eigenvectors. The eigenvectors are principal components (or individual modes of motion) that describe the essential dynamics of the protein complex.

From each mode of motion, individual fluctuations of alpha carbons can thus be obtained. Using these fluctuations, elements of dynamic cross-correlation matrices (DCCMs) can be constructed using the following equation:

Here, Cij is the cross-correlation value between residues i and j, ∆ri and ∆rj represent the positional fluctuations of alpha carbons in the respective modes of motion. The values of Cij range from -1 to 1, denoting the maximum levels of anti-correlation and correlation, respectively. To simplify the analysis and focus on the top global modes of motion that describe the majority of variance in motion, C matrices were computed for only the top 20 global modes of motion. A weighted average of these matrices was then computed using eigenvalues as weights to yield a single DCCM for each simulation trajectory.

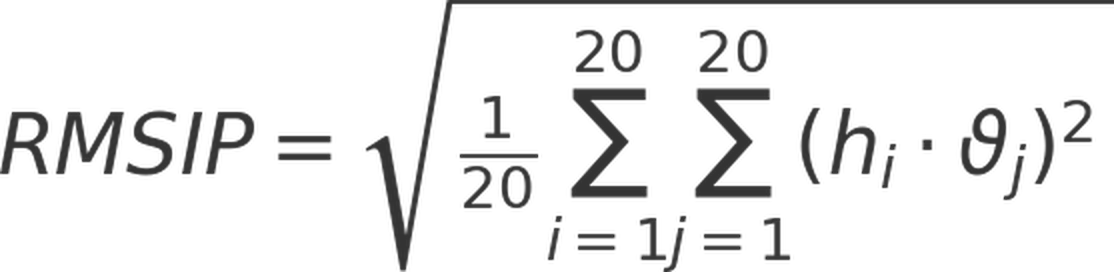

Root mean square inner products (RMSIPs), also termed subspace overlaps, of two simulation trajectories were also computed to quantify the levels of (dis)similarities between them, using the following equation:

Here, ηi and νj are eigenvectors associated with modes i and j, respectively.

Calculation of Pairwise Residue Interaction Energies

Non-bonded interaction energies between contacting amino acid pairs throughout the simulation trajectories were computed using a modified version of gRINN (get Residue Interaction eNergies and Networks) (28). First, a cutoff distance of 10 Å was used to identify pairs of amino acids to be included in the calculation, based on positions of their alpha carbons. Then, the “rerun” feature of gmx mdrun was used to compute non-bonded van der Waals and electrostatic interaction energies between these identified amino acid pairs. Energies were initially reported in kJ/mol by GROMACS and subsequently converted to kcal/mol before further analysis.

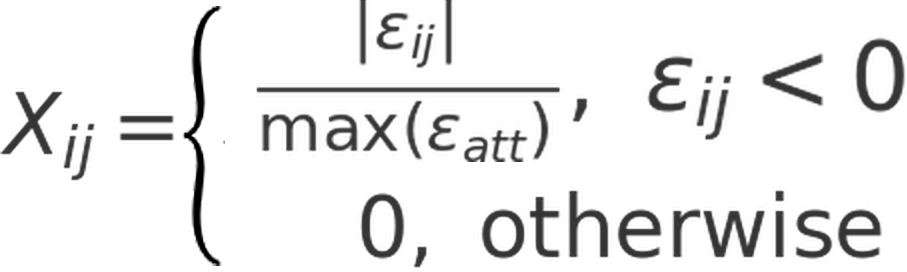

Construction of Protein Energy Networks

Once interaction energies were computed, a protein energy network (PEN) was constructed by taking each amino acid as a node, each interaction as an edge, and van der Waals interaction energies as an edge weight. Edges were added between two residues if they were covalently-bound or interacted with each other in the respective conformation with a van der Waals interaction energy of at least 1 kcal/mol in magnitude (either ≤ –1 kcal/mol or ≥ 1 kcal/mol). Edge weights were given a value of 1 if the two interacting pairs are covalently bound, and a value of Xij if otherwise. Xij was computed as follows:

Here, Xij is the edge weight, εij is the non-bonded van der Waals interaction energy, and εatt is the array of negative interaction energies. Using this formula enables the assignment of higher weights to more negative (or more attractive) interactions. A PEN was constructed for each conformation in the simulation trajectory. Once a PEN was constructed, betweenness-centralities (BCs) of each node were computed using Brandes’ algorithm (29), based on shortest paths identified using Dijkstra’s algorithm (30).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t-test were used as appropriate.

Tools and Software Packages

All analyses were performed within a Python-based data analysis environment using the following packages: NumPy (31), Matplotlib (32), Seaborn, Pandas, and ProDy (33).

Results

Weaker Interactions with the F Pocket Lead to Lower pMHC Conformational Stability

Three peptides (ALW, MVW, and RQW) bound to HLA-A*02:01 were studied using molecular dynamics simulations. Each system underwent three 750-ns simulations, including a peptide-free control as reference. The selection of these particular peptides was based on comprehensive experimental data reported by Hopkins et al. (31). This study is notable as it uniquely provides not only half-life measurements, indicative of thermal stability, but also detailed insights into the conformational flexibility of these pMHCs through high-pressure perturbation experiments. Such extensive experimental data, covering both stability and dynamic conformational responses, is uncommon in pMHC literature, where studies often report only affinity or thermal/cell surface stability, leaving the role of conformational flexibility less defined.

Given that all three pMHC systems (ALW, MVW, and RQW with HLA-A*02:01) were found to behave differently in high-pressure or temperature perturbation experiments and previous molecular dynamics simulations (31), they serve as ideal benchmarks for a more granular investigation of the effect of peptide binding on the overall pMHC structure, as intended here. Notably, the experimental data from Hopkins et al. (31) highlighted distinct biophysical characteristics for these peptides; for instance, the ALW-HLA-A*02:01 complex showed physicochemical indicators (a significantly higher ΔCp) suggestive of greater conformational flexibility compared to the others. Furthermore, these peptides are valuable benchmarks due to observed discrepancies between their experimental stability and affinity data and those predicted by standard computational tools, underscoring the need for detailed mechanistic studies. A detailed description of the characteristics of these peptides can be found in Supplementary Text.

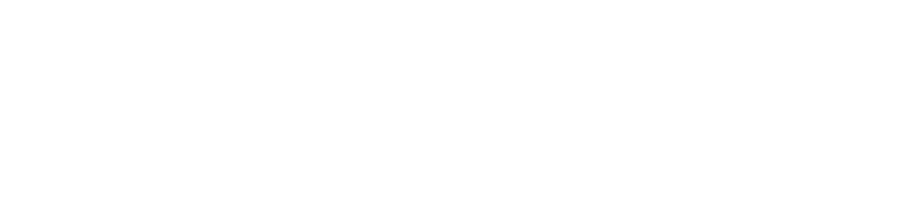

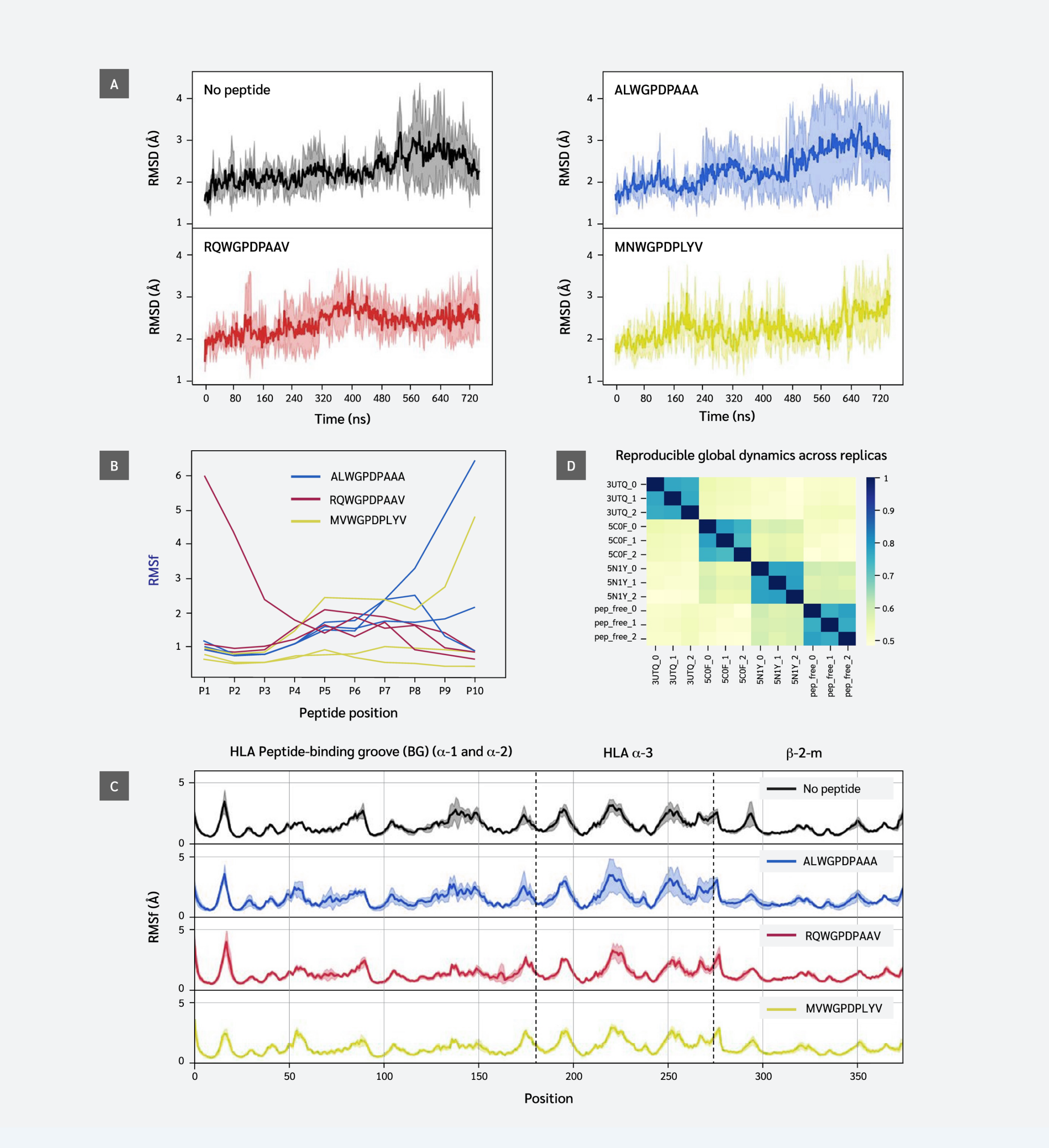

Figure 1A shows stable fluctuations after equilibration, with the ALW peptide and peptide-free system displaying higher fluctuation levels. This suggests ALW's effect on pMHC dynamics is less significant than that of other peptides. The effect on stability of the whole complex is often directly linked to the binding stability of the peptide throughout the simulations. To probe the stability of each peptide residue, we next computed the RMSF values of each peptide residue (position) in each simulation.

This analysis revealed partial peptide detachment in one simulation of each system: at the C-terminus (F pocket) for ALW and MVW, and at the N-terminus (B pocket) for RQW. In peptide-free and ALW simulations, HLA and β2m residues showed higher variation in positions 70-85 and 140-150, corresponding to α-1 and α-2 regions of the F pocket. Results indicate that strong peptide C-terminus-F-pocket interactions are crucial for conformational stability.

Peptide Ligand Leads to Reproducible Global Dynamics Profiles

Our findings showed that peptide sequence and interactions affect fluctuations of peptide and HLA residues, and influence regions beyond the peptide binding groove. This is not clearly visible in the RMSF plot (Figure 1C), except in parts of the α3 domain, possibly due to thermal fluctuations masking potential dynamic differences. We performed EDA of simulation trajectories to better understand similarities/differences between global dynamics profiles of different systems.

Essential dynamics analysis provides motional modes and their contributions to overall variance. We analyzed the top 20 motions describing global coordinated movements and calculated similarities between these modes using the RMSIP metric. Figure 1D shows that the replica simulations of each system exhibited the highest similarity, indicating strong reproducibility. This enables a reliable comparison between different systems. Subspace overlaps between different systems exhibit moderate similarity levels (0.5–0.6), indicating that while peptides do not create unique cooperative domain motions, they produce distinct motional profiles. RQW and MVW peptide simulations showed relatively higher similarities compared to others.

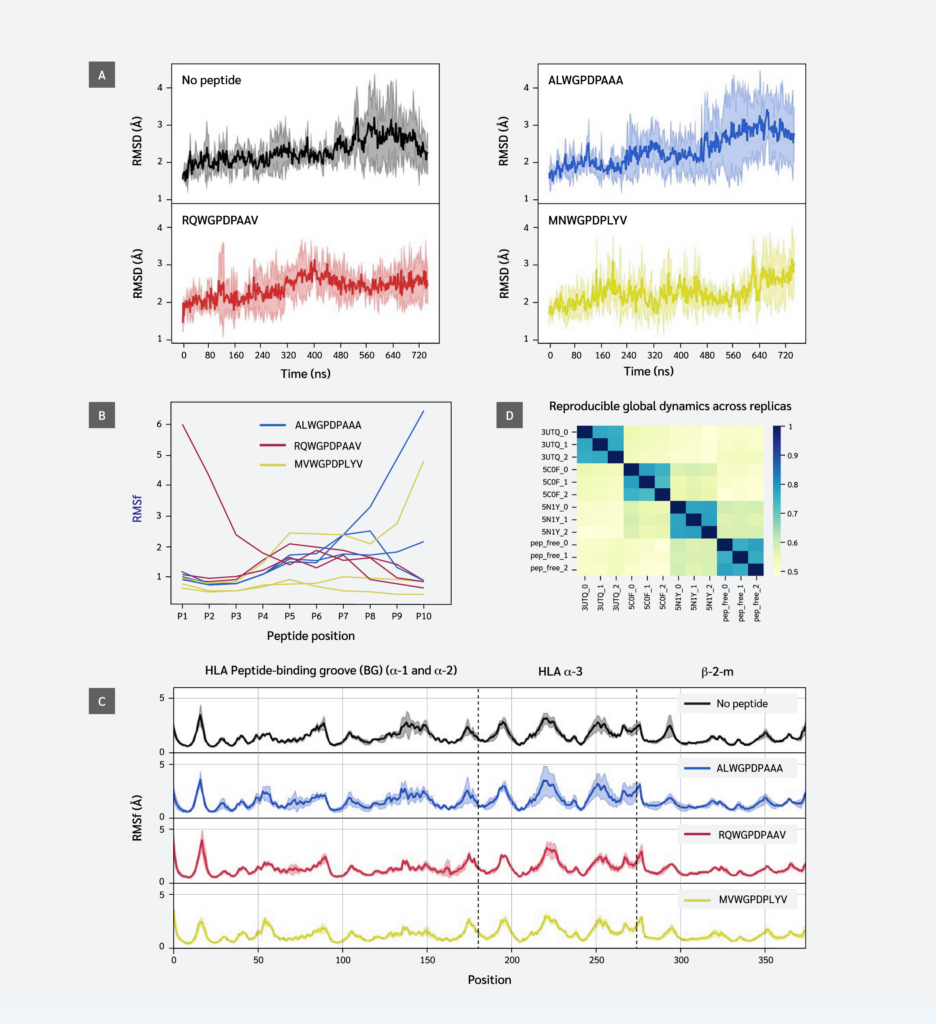

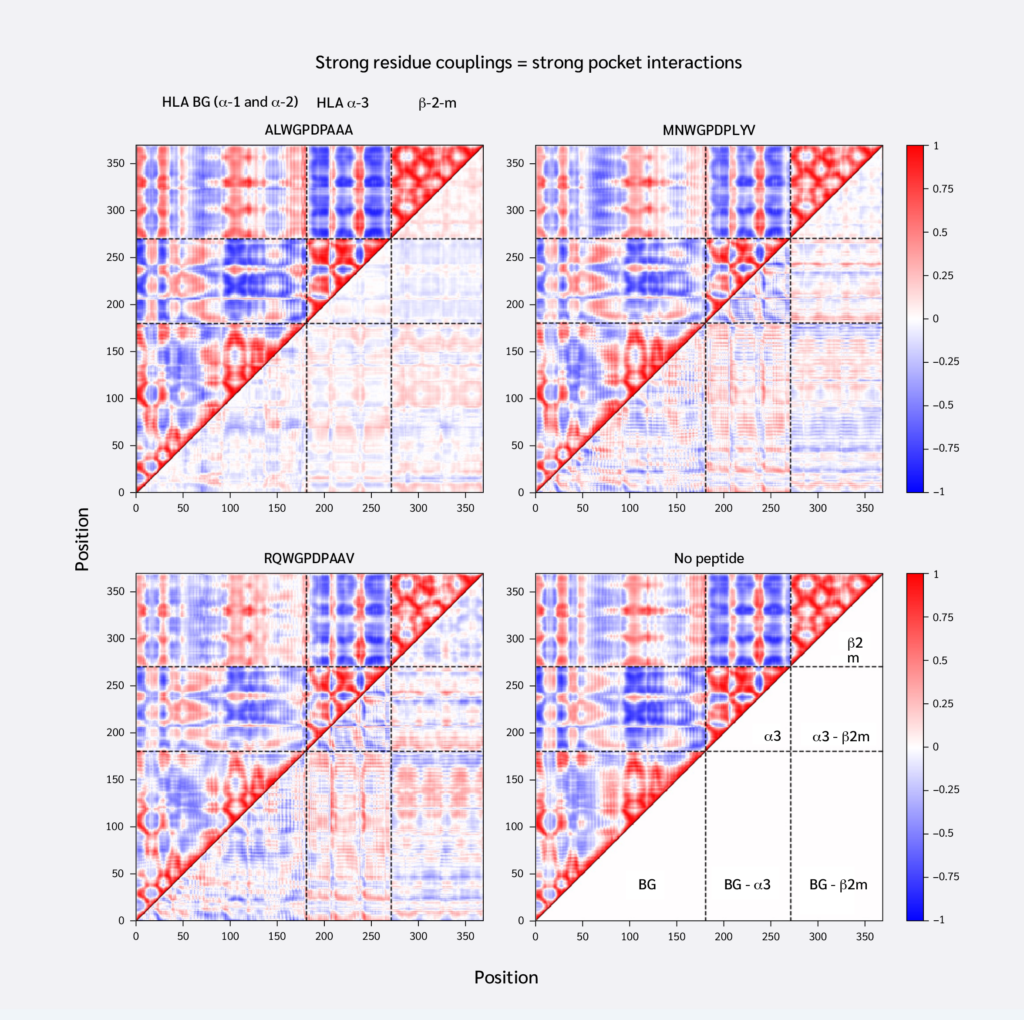

Stronger Peptide Binding in F Pocket Leads to More Extensive Changes in Dynamic Residue Couplings

Having confirmed that replica simulations explored similar essential subspaces, we next investigated residue couplings, comparing peptide-loaded and peptide-free systems. For this, we generated average DCCMs for each system using the top 20 global motional modes. Subtracting the DCCM of the peptide-free system from each peptide-loaded system yielded difference DCCMs (ΔDCMMs), visualizing changes in residue couplings upon peptide binding (Figure 2).

Consistent with similar RMSF profiles and RMSIP values above 0.5 (Figure 1D), the systems exhibited similar overall residue coupling profiles. However, ΔDCMM plots also revealed subtle peptide-specific differences. ALW binding induced relatively smaller coupling changes, increasing both correlations and anti-correlations between the HLA binding groove and α3/β2m. Notably, ALW binding showed minimal changes in intra-α3 couplings, with increased intra-β2m correlations but decreased β2m-α3 correlations.

Conversely, MVW and RQW exerted similar, but stronger, effects than ALW. They increased positive correlations between the HLA binding groove and α3/β2m, shifted intra-α3 couplings toward anti-correlation, and increased β2m-α3 coupling. In summary, stronger F pocket peptide binding led to more extensive changes in MHC dynamic coupling, particularly an increase in the positive correlation between the peptide-binding groove and distal domains.

Peptide Binding Induces Perturbations in

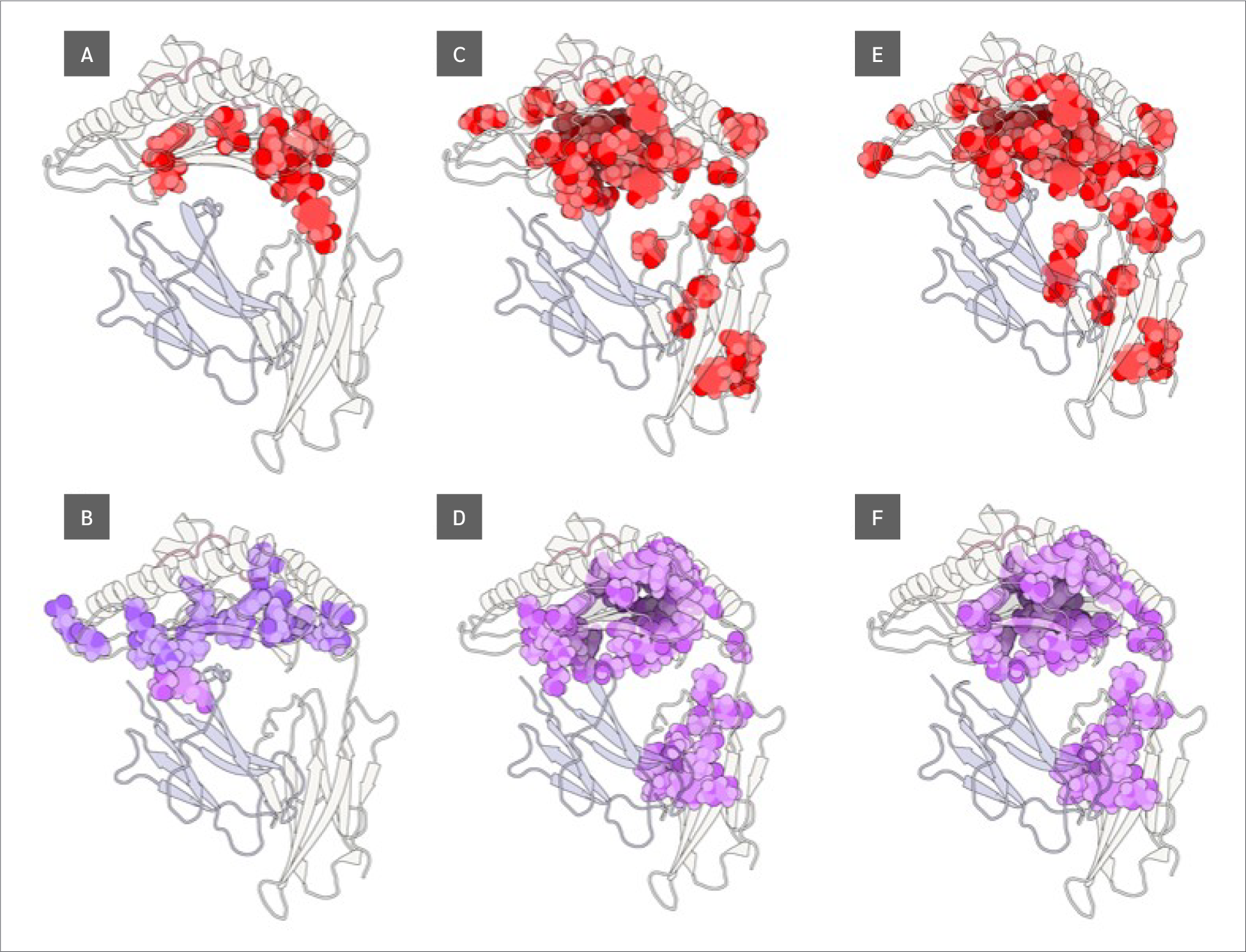

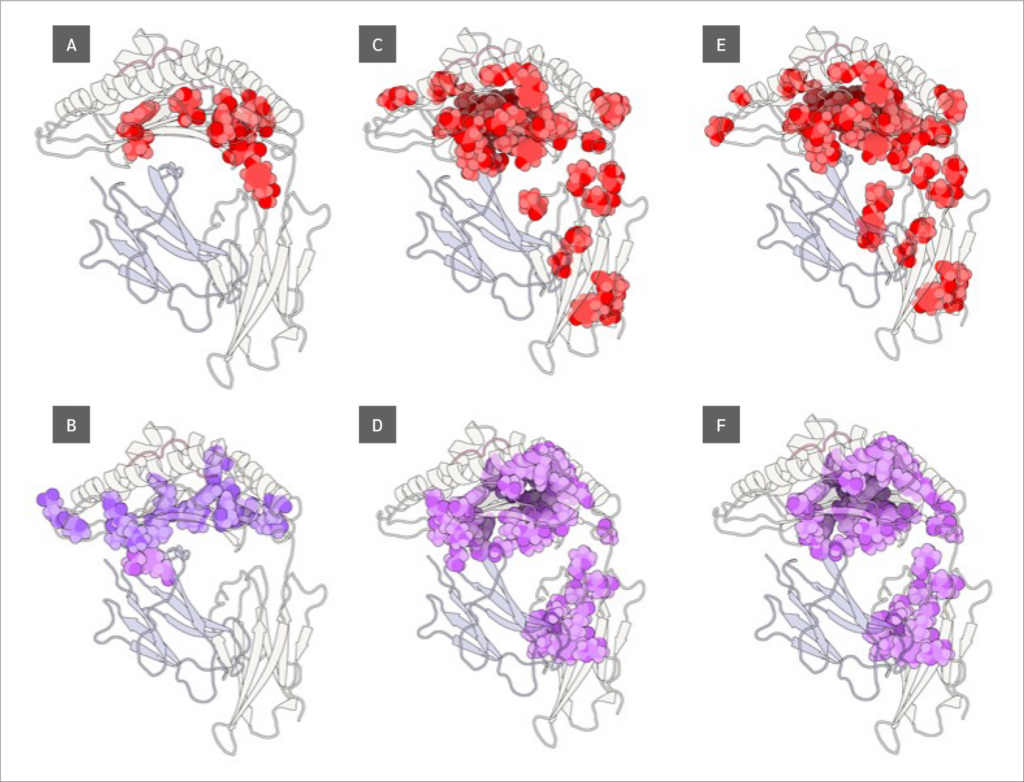

Intra- and Inter-Chain Residue Interaction Energies

We identified "consistent pairs" that exhibited significantly similar interaction energies across replicas using one-way ANOVA. In other words, pairs whose interaction energies did not differ significantly (p>0.05) across replica simulations (defined as those with a p-value > 0.05 from the ANOVA test) were identified (the full list of pairs and their corresponding p values can be found in Supplementary Data file under Tab “Consistent Pairs”). Finally, we identified pairs that showed statistically significant (p<0.05, Student’s t-test) energy shifts upon peptide binding, defined as those with a p-value < 0.05 from a Student’s t-test, and which also had with an absolute interaction energy difference of at least 2 kcal/mol upon peptide binding toward attractive or repulsive ranges (Figure 3) (the full list of pairs and their corresponding p values can be found in Supplementary Data file under Tab “Affected upon Peptide Binding”).

Strikingly, ALW exhibited a smaller effect compared to the other peptides. ALW induced shifts toward attraction only within the binding groove, not extending to distal domains or the β2m-α3 interface. It also caused shifts toward repulsion in this interface, decreasing attraction between Val12(BG)-Ser34(β2m) and Ile23(BG)-Phe63(β2m). Conversely, MVW and RQW showed much more extensive effects, both within the binding groove and on interacting pairs between β2m and α3, as well as at the bottom of the binding groove. Their effects were also highly similar, affecting the same pairs. Interactions becoming more attractive included Phe9(BG)-Phe57(β2m), Ser11(BG)-Glu55(β2m), and Tyr11(β2m)-Pro235(α3), while those becoming more repulsive included Val12(BG)-Ser34(β2m), Thr10(BG)-Gly56(β2m), and Val25(BG)-Gly56(β2m).

Stabilization of the F Pocket by Peptides Leads to Stabilized Interactions Near the Core of the MHC

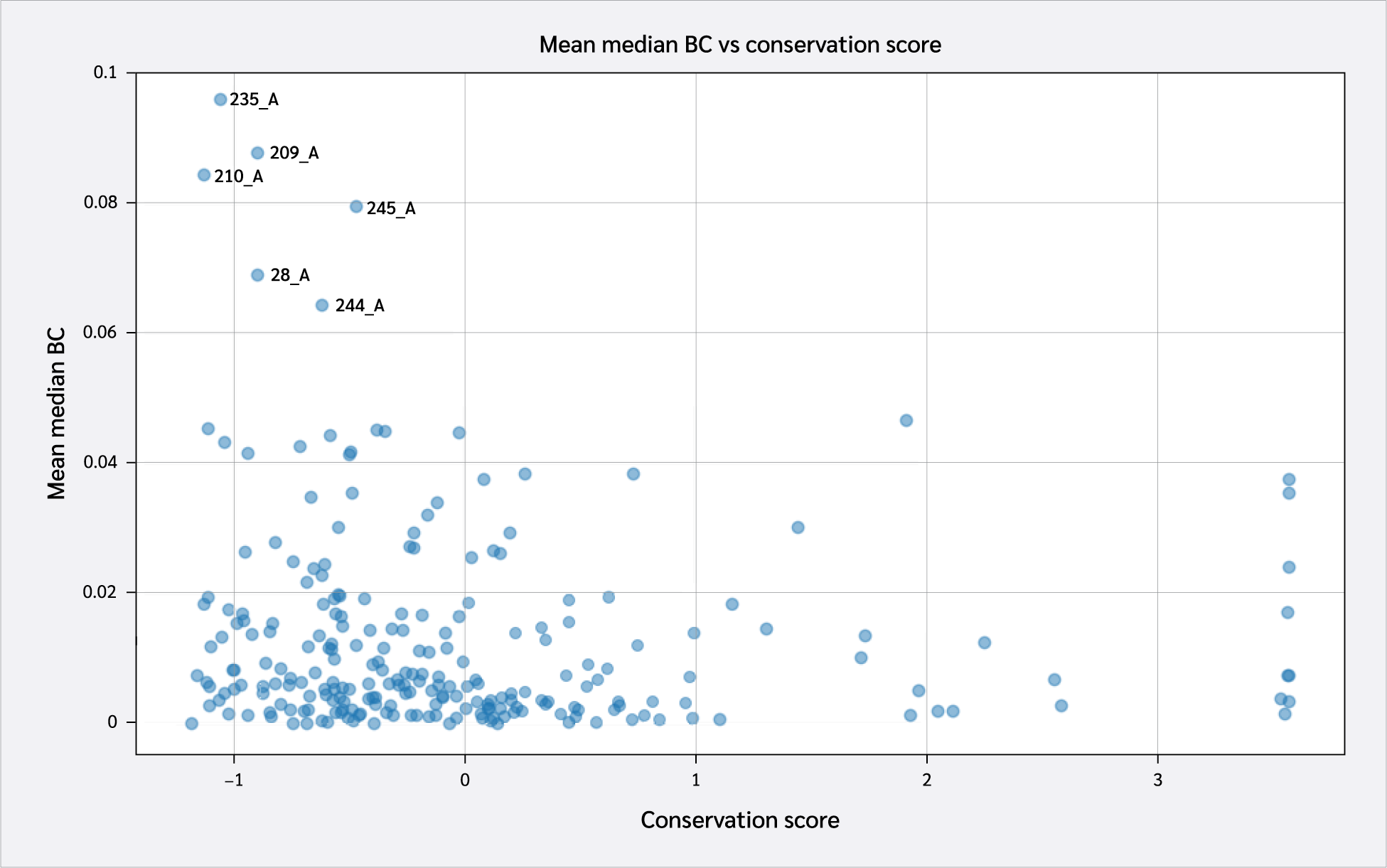

Motivated by the differential effects of peptides on the pMHC protein-protein interface, we investigated how these changes translate to individual residue behavior. Since edge weights reflect interaction attractiveness or repulsiveness, PENs are useful for probing stability. We computed betweenness centrality (BC) values for each residue, representing the average number of shortest paths through that residue. Here, residues with optimized interactions (and thus predominantly negative/attractive non-bonded interaction energies with their surroundings) have higher BC values.

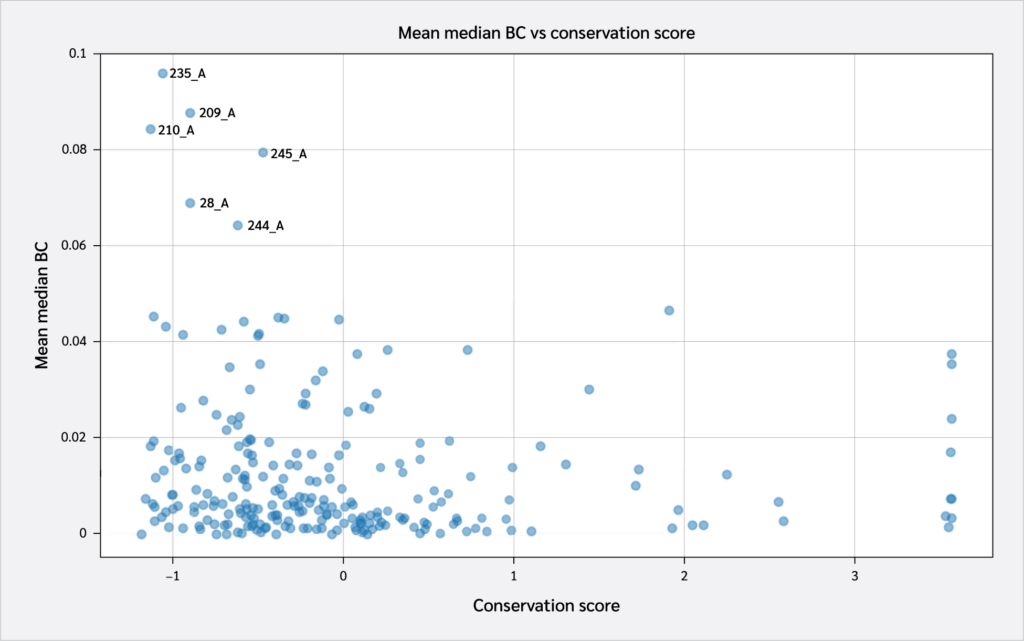

These scores were subsequently compared to overall residue conservation scores obtained from the CONSURF database (35). A scatter plot of conservation scores versus mean BC levels is shown in Figure 4. A key takeaway from this plot is the high conservation levels of HLA residues with the highest BC levels. These include Pro235(α3), Tyr209(α3), Pro210(α3), Trp244(α3), Ala245(α3), and Val28(BG).

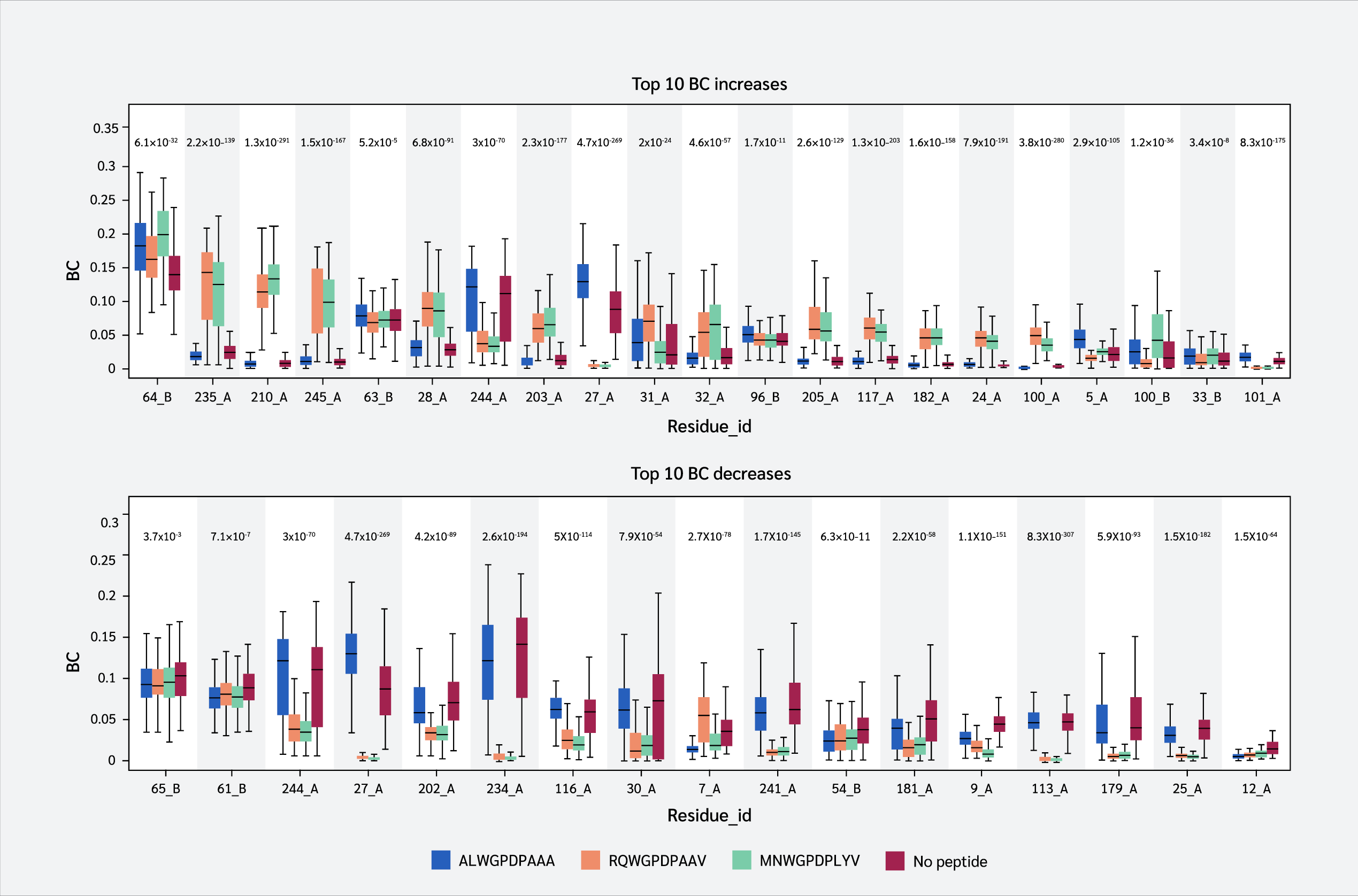

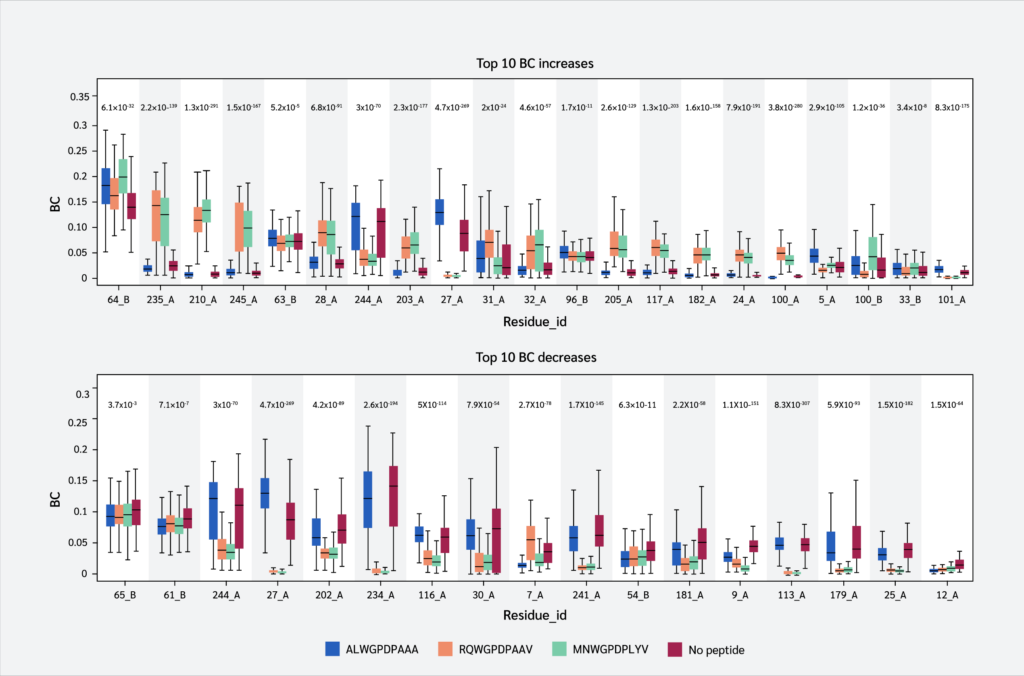

Finally, we identified residues with statistically significant BC differences between systems, which were defined as those having a p-value < 0.05 from a using one-way ANOVA test. From this group of significant residues, we (p<0.05) and selected the top 10 residues with the largest BC increases or decreases upon peptide binding (Figure 5), based on median BC levels (the full list of residues with their corresponding p values can be found in Supplementary Data file under Tab “Betweenness Centralities”).

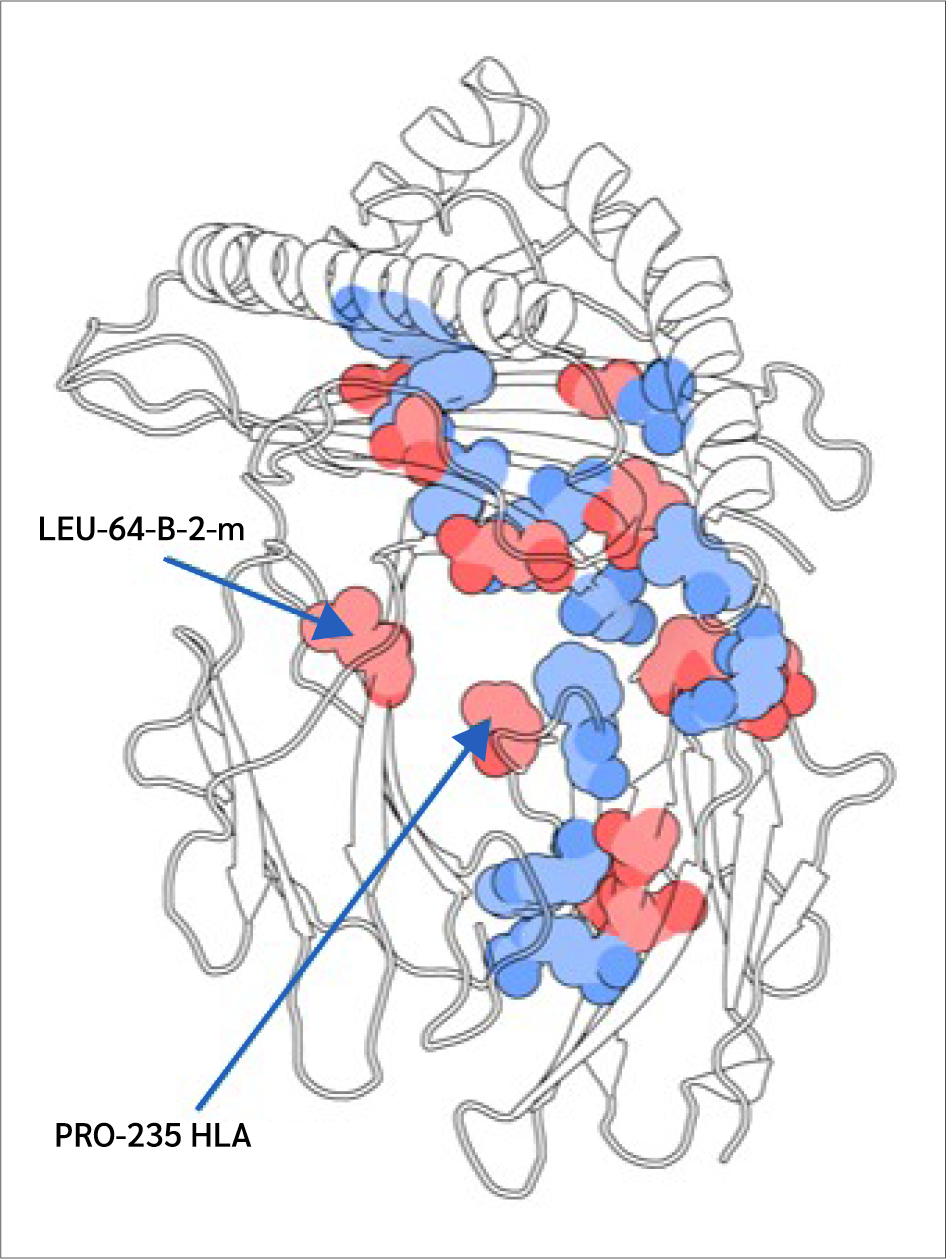

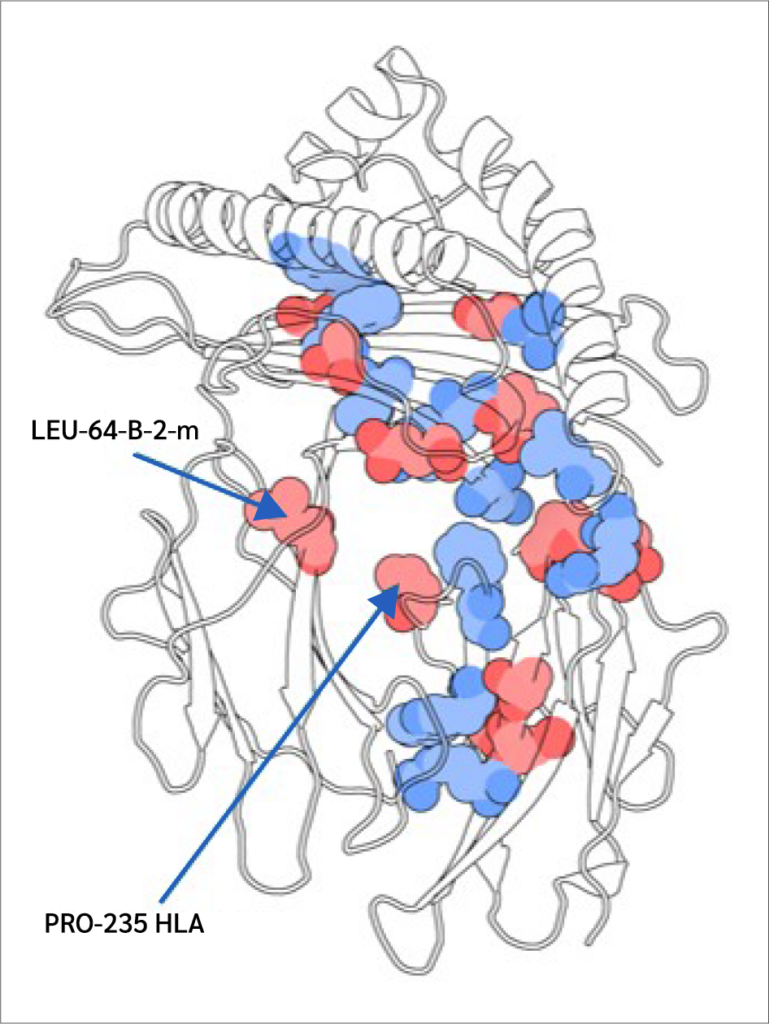

Two key findings emerged from this analysis. First, residues 64 B (β2m threonine) and 235 A (α3 proline), both located in distal domains (Figure 6), showed the largest BC increases upon peptide binding. All peptides increased 64 B's betweenness, suggesting an allosteric effect near the β2m/pMHC core, reinforcing surrounding interactions. However, 235 A's BC increase was observed only with RQW and MVW, not ALW.

The first finding leads to the second key finding: for most residues in Figure 4, BC patterns were shared between the ALW and peptide-free systems, as well as between the RQW and MVW peptides, consistent with the lack of structural effects upon ALW binding. Consequently, the behavior of Pro235(α3) is particularly noteworthy; its high mean BC as shown in Figure 4 underscores its general importance to the structural integrity of the complex, while its significant and selective increase in BC upon binding of the strongly stabilizing peptides RQW and MVW further pinpoints it as a key residue involved in mediating peptide-specific allosteric effects on pMHC stability.

Discussion

This study investigated the influence of different peptide ligands on the structural dynamics and conformational stability of HLA-A*02:01 using molecular dynamics simulations. Essential dynamics and protein energy network analyses provided insights into peptide-induced changes in MHC-I and the modulation of complex dynamics.

The stability of pMHC has long been recognized as a critical factor for immunogenicity (39,40). Consequently, characterization of pMHC stability is of great interest for immunotherapeutic applications (41). It is understood that peptide binding is not solely dictated by interactions within the peptide-binding groove. Instead, the entire MHC complex, including more distal domains, contributes to the binding event and the overall stability of the pMHC assembly (16,42). Indeed, previous simulation studies have shown the importance of regions beyond the canonical binding site in modulating peptide-MHC interactions (19,42).

Despite this broader understanding, a significant portion of computational studies aimed at predicting or characterizing pMHC stability has predominantly focused on the interactions within the peptide-binding groove. This focus is often a necessary simplification to enable predictions at larger scales (44-47). However, such a narrow perspective may overlook crucial contributions from other regions of the complex to its overall stability. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to employ molecular dynamics simulations to systematically evaluate pMHC stability with a specific focus on protein-protein interaction interfaces throughout the entire complex (e.g., the heavy chain-β2m interface and intramolecular domain contacts). This approach enabled the identification and characterization of allosteric mechanisms through which peptides differentially modulate stabilization across these distal interfaces, extending our understanding beyond direct peptide-groove interactions.

Our results are consistent with prior research that highlights the tight connection between peptide ligands and MHC-I. Peptides typically anchor deeply into the MHC-I binding groove, resulting in MHC-I stability and flexibility depending on the peptide cargo (49). Peptide-free MHC is known to be unstable (49), and peptide binding stabilizes and dampens complex dynamics, affecting distal β2m and α3 domains. MHC conformational stability depends on peptide C-terminus interactions with the F-pocket (50). Our findings offer new insights into this stabilization. We have shown that stable F-pocket binders (MVW and RQW) induce larger increases in positive correlations between the binding groove and α3, as well as in both positive and negative correlations between the binding groove and β2m. This strengthens crosstalk between distal domains and the binding groove, potentially through increased attraction between HLA and β2m, as revealed by our non-bonded interaction energy analysis. Weaker ALW binding even increased repulsiveness at the β2m-HLA interface.

The highly polymorphic nature of MHC-I molecules has significant implications for their structural dynamics and stability (20,51-53). Certain MHC alleles are more dependent on the chaperone protein Tapasin for proper peptide loading compared to others (54-57). Micropolymorphisms within the F-pocket region of the peptide-binding groove may lead to differential dependencies on Tapasin for binding of high-affinity peptides (57-60). These subtle sequence variations in the F-pocket can lead to distinct global conformational dynamics of the MHC complex, even in the peptide-free state. Specifically, some F-pocket polymorphisms may favor a more stable and rigid conformation of the MHC, while others may result in a more flexible and dynamic structure (61). This allele-specific behavior of the peptide-free MHC likely has consequences for the conformational stabilization induced by the binding of different peptide ligands, as observed in our findings. Future studies that explore the interplay among F-pocket polymorphisms, Tapasin dependency, global dynamics, and complex stability will provide valuable context for interpreting the conformational stabilization mechanisms revealed by our molecular dynamics’ simulations.

Furthermore, major stability differences among HLA genes themselves may also imply differential behaviour to peptide binding. For instance, HLA-C alleles are known to exhibit lower cell surface expression and stability levels compared to HLA-A and HLA-B alleles (62,63). This reduced stability of HLA-C has also been associated with less efficient responses against viral infections (64). Our previous local frustration analysis of human MHC-I allele structures highlighted a less stable F pocket in HLA-C (65). Weaker interactions between the F pocket and peptide cargo may thus represent a general phenomenon in HLA-C, resulting in a failure to strengthen interactions with distal domains of the complex, as observed in the case of the ALW peptide in this study.

Finally, it is important to note that we did not observe a strong correlation between experimental or theoretical measures of thermal stability (i.e., melting temperature) or kinetic stability (i.e., half-time) and our findings related to conformational stability (see Supplementary Text). This may be explained by discrepancies between experimental measurements on the same peptide-HLA pair, or, more specifically, a lack of sufficient data points, which restricts the reliability of such comparisons. Alternatively, the thermal and conformational stability of MHC molecules may not be directly related, as is also the case for many other proteins (66,67). Previous work in this field has explored both kinetic (i.e., over time) and thermal stability of pMHC, and a positive correlation between these two types of stability metrics has been identified (68,69). It is also worth emphasizing that classical MD simulations in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble (i.e., at constant temperature and pressure) are inherently limited to mimic experimental conditions used in both types of stability measurements since simulations cover neither the full-time scale (often hours) nor the temperature ranges (increased over time) used in these experiments. To this end, predicting and evaluating MHC thermal stability alongside molecular simulation findings remains a challenge. Application of a similar computational strategy to a higher number of pMHC complexes with reliable experimental structures and both thermal and kinetic stability data may lead to more comprehensive insights into peptide-induced stabilization in this regard.

Conclusion

In summary, this study highlights the intricate relationship between peptide ligands and the conformational dynamics of HLA-A*02:01, emphasizing the crucial role of stable interactions within the F-pocket for achieving structural integrity and stability. The observed enhancements in dynamic coupling and crosstalk between the peptide-binding groove and distal domains underscore the complexity of MHC-I-peptide interactions and their influence on overall protein behavior. These enhancements may result in a shift of attractive interactions towards the HLA-β2m interface, ultimately contributing to increased conformational stability of the whole complex. To this end, our findings also challenge the assumption that thermal stability directly correlates with conformational stability, highlighting the need for further research to elucidate these relationships. The insights gained from our molecular dynamics simulations not only reinforce existing literature but also pave the way for future studies aimed at understanding the nuances of MHC-peptide interactions, which could ultimately inform therapeutic strategies in immunology and vaccine development.

Ethical Approval

N.A.

Informed Consent

N.A.

Peer-review

Externally peer-reviewed

Author Contributions

Concept – O.S.; Design – O.S.; Supervision – O.S.; Fundings – O.S.; Materials – O.S.; Data Collection and/or Processing – O.S.; Analysis and/or Interpretation – O.S.; Literature Review – O.S.; Writer – O.S.; Critical Reviews – O.S.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure

The author declared that this study has received no financial support.

Data Availability

The data tables generated through analysis of MD simulation trajectories conducted, including all p values, can be found at Zenodo at the following URL: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14651951. These data tables were used to generate figures presented in the manuscript.

Declaration Regarding the Use of AI and AI-Assisted Technologies

During the preparation of this work, the author utilized Jenni (jenni.ai) to create an initial draft of the introduction section. After carefully reviewing and editing the content as necessary, full responsibility for the publication's content is taken by the author. This incorporation of AI tool usage primarily impacted the flow of information and readability of the introduction section only.

Acknowledgment

he author would like to thank Malgorzata A. Garstka for her insightful comments on peptide-induced MHC stability and MHC-Tapasin interactions, which substantially improved the depth and clarity of the analyses presented in this study.

References

Hermens JM, Kesmir C. Role of T cells in severe COVID-19 disease, protection, and long term immunity. Immunogenetics. 2023;75(3):295-307. [CrossRef]

Raskov H, Orhan A, Christensen JP, Gögenur I. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(2):359-67. [CrossRef]

Amigorena S. Antigen presentation: from cell biology to physiology. Immunol Rev. 2016;272(1):5-7. [CrossRef]

Parham P. Putting a face to MHC restriction. J Immunol. 2005;174(1):3-5. [CrossRef]

Nesmiyanov PP. Antigen presentation and major histocompatibility complex. In: Rezaei N, editor. Encyclopedia of Infection and Immunity. 1st ed. Elsevier; 2022. p.90-98. [CrossRef]

Kotsias, F, Cebrian, I, Alloatti, A. Antigen processing and presentation. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 2019;348:69-121. [CrossRef]

Chiou, SJ, Chen, CH. Decipher β2-microglobulin: gain- or loss-of-function (a mini-review). Medical Science Monitor Basic Research, 2013;19:271–3. [CrossRef]

Solheim, JC. Class I MHC molecules: assembly and antigen presentation. Immunological Review. 1999;172:11–9. [CrossRef]

Fodor J, Riley BT, Borg NA, Buckle AM. Previously hidden dynamics at the TCR-peptide-MHC interface revealed. J Immunol. 2018;200(12):4134-45. [CrossRef]

Natarajan K, Jiang J, May NA, Mage MG, Boyd LF, McShan AC, et al. The role of molecular flexibility in antigen presentation and T cell receptor-mediated signaling. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1657. [CrossRef]

Jantz-Naeem N, Springer S. Venus flytrap or pas de trois? The dynamics of MHC class I molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 2021;70:82-9. [CrossRef]

Ayres CM, Baker BM. Peptide-dependent tuning of major histocompatibility complex motional properties and the consequences for cellular immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2022;76:102184. [CrossRef]

Borbulevych OY, Piepenbrink KH, Gloor BE, Scott DR, Sommese RF, Cole DK, et al. T cell receptor cross-reactivity directed by antigen-dependent tuning of peptide-MHC molecular flexibility. Immunity. 2009;31(6):885-96. [CrossRef]

Nguyen AT, Szeto C, Gras S. The pockets guide to HLA class I molecules. Biochem Soc Trans. 2021;49(5):2319-31. [CrossRef]

Yanaka S, Ueno T, Shi Y, Qi J, Gao GF, Tsumoto K, et al. Peptide-dependent conformational fluctuation determines the stability of the human leukocyte antigen class I complex. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(35):24680-90. [CrossRef]

Dirscherl C, Löchte S, Hein Z, Kopicki JD, Harders AR, Linden N, et al. Dissociation of β2m from MHC class I triggers formation of noncovalent transient heavy chain dimers. J Cell Sci. 2022;135(9):jcs259489. [CrossRef]

Harndahl M, Rasmussen M, Roder G, Buus S. Real-time, high-throughput measurements of peptide-MHC-I dissociation using a scintillation proximity assay. J Immunol Methods. 2011;374(1-2):5-12. [CrossRef]

Bingöl EN, Serçinoğlu O, Ozbek P. Unraveling the allosteric communication mechanisms in T-cell receptor-peptide-loaded major histocompatibility complex dynamics using molecular dynamics simulations: An approach based on dynamic cross correlation maps and residue interaction energy calculations. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61(5):2444-53. [CrossRef]

Serçinoğlu O, Ozbek P. Computational characterization of residue couplings and micropolymorphism-induced changes in the dynamics of two differentially disease-associated human MHC class-I alleles. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2018;36(3):724-40. [CrossRef]

Amarajeewa AWP, Özcan A, Mukhtiar A, Ren X, Wang Q, Ozbek P, et al. Polymorphism in F pocket affects peptide selection and stability of type 1 diabetes-associated HLA-B39 allotypes. Eur J Immunol. 2024;54(6):e2350683. [CrossRef]

Knapp B, Demharter S, Esmaielbeiki R, Deane CM. Current status and future challenges in T-cell receptor/peptide/MHC molecular dynamics simulations. Brief Bioinform. 2015;16(6):1035-44. [CrossRef]

Alba J, D'Abramo M. The full model of the pMHC-TCR-CD3 complex: A structural and dynamical characterization of bound and unbound states. cells. 2022;11(4):668. [CrossRef]

Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1-2:19-25. [CrossRef]

Hopkins CW, Le Grand S, Walker RC, Roitberg AE. Long-time-step molecular dynamics through hydrogen mass repartitioning. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11(4):1864-74. [CrossRef]

Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Klepeis JL, Dror RO, et al. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins. 2010;78(8):1950-8. [CrossRef]

Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235-42. [CrossRef]

Bulek AM, Cole DK, Skowera A, Dolton G, Gras S, Madura F, et al. Structural basis for the killing of human beta cells by CD8(+) T cells in type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(3):283-9. [CrossRef]

Serçinoglu O, Ozbek P. gRINN: a tool for calculation of residue interaction energies and protein energy network analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W554-62. [CrossRef]

Brandes U. A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. J Math Sociol. 2001;25(2):163-77. [CrossRef]

Dijkstra EW. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. Numer Math. 1959;1(1):269-71. [CrossRef]

Harris CR, Millman KJ, van der Walt SJ, Gommers R, Virtanen P, Cournapeau D, et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature. 2020;585(7825):357-62. [CrossRef]

Hunter JD. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput Sci Eng. 2007;9(3):90-5. [CrossRef]

Zhang S, Krieger JM, Zhang Y, Kaya C, Kaynak B, Mikulska-Ruminska K, et al. ProDy 2.0: increased scale and scope after 10 years of protein dynamics modelling with Python. Bioinformatics. 2021;37(20):3657-9. [CrossRef]

Hopkins JR, Crean RM, Catici DAM, Sewell AK, Arcus VL, Van der Kamp MW, et al. Peptide cargo tunes a network of correlated motions in human leucocyte antigens. FEBS J. 2020;287(17):3777-93. [CrossRef]

Vijayabaskar MS, Vishveshwara S. Interaction energy based protein structure networks. Biophys J. 2010;99(11):3704-15. [CrossRef]

Yan W, Sun M, Hu G, Zhou J, Zhang W, Chen J, et al. Amino acid contact energy networks impact protein structure and evolution. J Theor Biol. 2014;355:95-104. [CrossRef]

Yehorova D, Di Geronimo B, Robinson M, Kasson PM, Kamerlin SCL. Using residue interaction networks to understand protein function and evolution and to engineer new proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2024;89:102922. [CrossRef]

Ben Chorin A, Masrati G, Kessel A, Narunsky A, Sprinzak J, Lahav S, et al. ConSurf-DB: An accessible repository for the evolutionary conservation patterns of the majority of PDB proteins. Protein Sci. 2020;29(1):258-67. [CrossRef]

van der Burg SH, Visseren MJ, Brandt RM, Kast WM, Melief CJ. Immunogenicity of peptides bound to MHC class I molecules depends on the MHC-peptide complex stability. J Immunol. 1996;156(9):3308-14.

Harndahl M, Rasmussen M, Roder G, Dalgaard Pedersen I, Sørensen M, Nielsen M, et al. Peptide-MHC class I stability is a better predictor than peptide affinity of CTL immunogenicity. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(6):1405-16. [CrossRef]

Jappe EC, Garde C, Ramarathinam SH, Passantino E, Illing PT, Mifsud NA, et al. Thermostability profiling of MHC-bound peptides: a new dimension in immunopeptidomics and aid for immunotherapy design. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6305. [CrossRef]

Omasits U, Knapp B, Neumann M, Steinhauser O, Stockinger H, Kobler R, et al. Analysis of key parameters for molecular dynamics of pMHC molecules. Mol Simul. 2008;34(8):781-93. [CrossRef]

Rasmussen M, Fenoy E, Harndahl M, Kristensen AB, Nielsen IK, Nielsen M, et al. Pan-specific prediction of peptide-MHC class I complex stability, a correlate of T cell immunogenicity. J Immunol. 2016;197(4):1517-24. [CrossRef]

Abella JR, Antunes DA, Clementi C, Kavraki LE. Large-scale structure-based prediction of stable peptide binding to class I HLAs using random forests. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1583. [CrossRef]

Chieochansin T, Sanachai K, Darai N, Chiraphapphaiboon W, Choomee K, Yenchitsomanus PT, et al. In silico advancements in Peptide-MHC interaction: A molecular dynamics study of predicted glypican-3 peptides and HLA-A*11:01. Heliyon. 2024;10(17):e36654. [CrossRef]

Rostamian M, Farasat A, Chegene Lorestani R, Nemati Zargaran F, Ghadiri K, et al. Immunoinformatics and molecular dynamics studies to predict T-cell-specific epitopes of four Klebsiella pneumoniae fimbriae antigens. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40(1):166-76. [CrossRef]

Bunsuz A, Serçinoğlu O, Ozbek P. Computational investigation of peptide binding stabilities of HLA-B*27 and HLA-B*44 alleles. Comput Biol Chem. 2020;84:107195. [CrossRef]

Ayres CM, Abualrous ET, Bailey A, Abraham C, Hellman LM, Corcelli SA, et al. Dynamically driven allostery in MHC proteins: Peptide-dependent tuning of class I MHC global flexibility. Front Immunol. 2019;10:966. [CrossRef]

Theodossis A. On the trail of empty MHC class-I. Mol Immunol. 2013;55(2):131-4. [CrossRef]

Abualrous ET, Saini SK, Ramnarayan VR, Ilca FT, Zacharias M, Springer S. The carboxy terminus of the ligand peptide determines the stability of the MHC class I molecule H-2Kb: A combined molecular dynamics and experimental study. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135421. [CrossRef]

Serçinoğlu O, Ozbek P. Sequence-structure-function relationships in class I MHC: A local frustration perspective. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232849. [CrossRef]

Narzi D, Becker CM, Fiorillo MT, Uchanska-Ziegler B, Ziegler A, Böckmann RA. Dynamical characterization of two differentially disease associated MHC class I proteins in complex with viral and self-peptides. J Mol Biol. 2012;415(2):429-42. [CrossRef]

Bailey A, Dalchau N, Carter R, Emmott S, Phillips A, Werner JM, et al. Selector function of MHC I molecules is determined by protein plasticity. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14928. [CrossRef]

van Hateren A, Elliott T. The role of MHC I protein dynamics in tapasin and TAPBPR-assisted immunopeptidome editing. Curr Opin Immunol. 2021;70:138-43. [CrossRef]

Badrinath S, Huyton T, Blasczyk R, Bade Doeding C, et al. HLA class I polymorphism and tapasin dependency. In: HLA and Associated Important Diseases. Rezaei N, editor. London: InTech; 2014. p. X Y. [CrossRef]

Aflalo A, Boyle LH. Polymorphisms in MHC class I molecules influence their interactions with components of the antigen processing and presentation pathway. Int J Immunogenet. 2021;48(4):317-25. [CrossRef]

Wieczorek M, Abualrous ET, Sticht J, Álvaro-Benito M, Stolzenberg S, Noé F, et al. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and MHC class II proteins: Conformational plasticity in antigen presentation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:292. [CrossRef]

Abualrous ET, Fritzsche S, Hein Z, Al-Balushi MS, Reinink P, Boyle LH, et al. F pocket flexibility influences the tapasin dependence of two differentially disease-associated MHC Class I proteins. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(4):1248-57. [CrossRef]

Garstka MA, Fritzsche S, Lenart I, Hein Z, Jankevicius G, Boyle LH, et al. Tapasin dependence of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules correlates with their conformational flexibility. FASEB J. 2011;25(11):3989-98. [CrossRef]

Garstka MA, Fish A, Celie PH, Joosten RP, Janssen GM, Berlin I, et al. The first step of peptide selection in antigen presentation by MHC class I molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(5):1505-10. [CrossRef]

Fisette O, Schröder GF, Schäfer LV. Atomistic structure and dynamics of the human MHC-I peptide-loading complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(34):20597-606. [CrossRef]

Neisig A, Melief CJ, Neefjes J. Reduced cell surface expression of HLA-C molecules correlates with restricted peptide binding and stable TAP interaction. J Immunol. 1998;160(1):171-9.

Kaur G, Gras S, Mobbs JI, Vivian JP, Cortes A, Barber T, et al. Structural and regulatory diversity shape HLA-C protein expression levels. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15924. [CrossRef]

Vigón L, Galán M, Torres M, Martín-Galiano AJ, Rodríguez-Mora S, Mateos E, et al; Multidisciplinary Group of Study of COVID-19 (MGS-COVID). Association between HLA-C alleles and COVID-19 severity in a pilot study with a Spanish Mediterranean Caucasian cohort. PLoS One. 2022;17(8):e0272867. [CrossRef]

Serçinoğlu O, Ozbek P. Sequence-structure-function relationships in class I MHC: A local frustration perspective. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232849. [CrossRef]

Karshikoff A, Nilsson L, Ladenstein R. Rigidity versus flexibility: the dilemma of understanding protein thermal stability. FEBS J. 2015;282(20):3899-917. [CrossRef]

Hou XN, Song B, Zhao C, Chu WT, Ruan MX, Dong X, et al. Connecting protein millisecond conformational dynamics to protein thermal stability. JACS Au. 2024;4(8):3310-20. [CrossRef]

Jappe EC, Garde C, Ramarathinam SH, Passantino E, Illing PT, Mifsud NA, et al. Thermostability profiling of MHC-bound peptides: a new dimension in immunopeptidomics and aid for immunotherapy design. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6305. [CrossRef]

Blaha DT, Anderson SD, Yoakum DM, Hager MV, Zha Y, Gajewski TF, et al. High-throughput stability screening of neoantigen/HLA complexes improves immunogenicity predictions. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(1):50-61. [CrossRef]

VOLUME

,

ISSUE

Correspondence

Received

Accepted

Published

Suggested Citation

DOI

License